This is part of Mindstream’s editorial package on Mental Wellbeing surrounding Episode 8 of The Mindstream Podcast.

By Liza Horan, Editor

The earliest notion of wellbeing in recorded history goes back to the Greek philosophers. There’s a series of books based on scrolls that captures notes from Aristotle’s lectures. The first is called, “The Nicomachean Ethics.” His concept of wellbeing was called eudaimonia, which is about living one’s one highest level of virtue — achieving the best of what is within each of us. And since the distinguishing factor of man versus animal is the ability to reason, eudaimonia is about “rational activity performed virtuously,” according to Britannica.com.

Some scholars say that eudaimonia has wrongly been labelled as “happiness,” and that wellbeing is what we ought to cultivate in this life, rather than this notion of happiness because hedonism can bring happiness, though it’s often simply momentary.

Eudaimonia, or a ‘state of good spirit’ according to Aristotle, is about growth, meaning, authenticity and excellence within one’s self, and hedonia is about pleasure, enjoyment, comfort and the absence of distress.

The pandemic delivered a crash-course in how to protect ourselves and others from thoughts and feelings that can come with fear, stress and isolation. Learning how to cope with imposed lifestyle changes and life-and-death matters has been a personal and collective experience.

The good news is that “mental health” has been normalized as a topic in conversation — it’s openly everyone’s concern now. The challenge is that there are lots of terms floating around, which can be confusing.

ICON Eliricon/Noun Project

What’s the difference between mental health, mental illness, mental disorder, mental wellness, mental wellbeing, emotional wellbeing, mental toughness, mental strength, self-care, contentment, and happiness — and where does self-care end and medical diagnosis begin?

My research of these terms, unfortunately, did not lead to a definitive glossary — but it did reveal that “mental wellbeing” is overtaking “mental health” as the go-to term to describe the state of our intellectual and emotional experience. This more positive framing overcomes the negative bias that “mental health” has picked up. And it’s a good move because words are are powerful: Research shows that we respond to language (for good or bad) whether we realise it or not. The Mental Health Foundation (UK) says, “Words are a barrier to help-seeking and a motivator for making discrimination acceptable.”

I live in Scotland, and “wellbeing” is a word uttered by our Prime Minister Nicola Sturgeon as well as holistic practitioners, coaches, therapists, and health charities. One such charity is Wellbeing Scotland. Since 1994, they have helped children and adults whose life experiences have impacted negatively on their wellbeing, particularly through abuse and trauma. The organisation provides client-centred holistic therapeutic services. When I recently met Chief Executive Janine Rennie, she told me that naming the charity Wellbeing Scotland was a deliberate choice: “The focus on wellbeing rather than illness is very important for recovery and for the recognition that we all need mental wellbeing.”

The Global Wellness Institute‘s report, “Defining the Mental Wellness Economy,” investigated all the terms and put forth a clear guide for language. Most significantly, the researchers surmised that “mental health” is a scientific and objective term used by the medical industry, and “mental wellbeing” is a personal and subjective term. So, one’s ‘mental status quo’ can be assessed in both ways, together. That means it’s possible to have a diagnosed mental illness yet feel content. Listen to GWI researcher Katherine Johnstone’s interview on the report in Episode 8 of The Mindstream Podcast.

GLOSSARY

Here’s a quick guide to some basic terms, and evidence of the shift to “mental wellbeing.”

Health is “soundness and vigor” and “freedom from disease or ailment,” whether in body or mind. (Dictionary.com)

Mental means “of or relating to the total emotional and intellectual response of an individual to external reality” (Merriam-Webster).

Mental Health definitions range meaning a neutral description — “health” means the status could be negative or positive, depending on how you feel at the moment — or it can suggest a positive state. It means “psychological wellbeing and satisfactory adjustment to society and to the ordinary demands of life” (Dictionary.com). The WHO Regional Office for Europe goes a step further, defining “mental health” as a state of wellbeing in which an individual can realise his or her own potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and make a contribution to the community.

Mental Illness and Serious Mental Illness are medical terms. The first can mean no or minimal impairment for a person, and the latter means “serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities,” according to the National Institute of Health. “Serious” can mean schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or long-term recurring major depression (source).

The Global Wellness Institute’s report, “Defining the Mental Wellness Economy,” is the first of its kind. It’s free to read here.

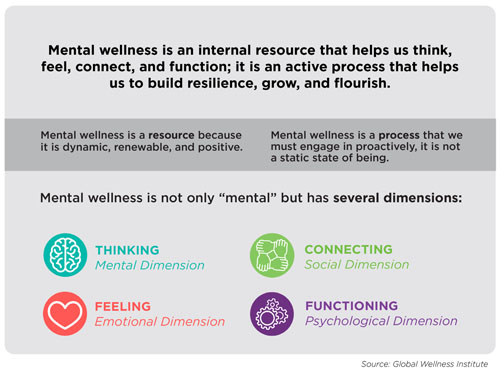

Mental Wellness is an “internal resource that helps us think, feel, connect, and function; it is an active process that helps us to build resilience, grow, and flourish,” according to the Global Wellness Industry’s landmark November 2020 report, “Defining the Mental Wellbeing Economy.” There are four major components to mental wellness: Thinking (how we process, understand and use information), Feeling (how we manage and express our feelings), Connecting (how we connect with others) and Functioning (how we “put the pieces together” to make decisions or do things).

Emotional Wellbeing has been defined as, “an overall positive state of one’s emotions, life satisfaction, sense of meaning and purpose, and ability to pursue self-defined goals. Elements of emotional well-being include a sense of balance in emotion, thoughts, social relationships, and pursuits,” by the U.S. National Institute of Health.

Wellbeing, in the simplest terms, is “the state of being comfortable, healthy or happy” (Oxford University Language).

Happiness generally is defined as “subjective wellbeing.” Positive psychology researcher and author of “The How of Happiness” Sonja Lyubomirsky described it as, “the experience of joy, contentment, or positive well-being, combined with a sense that one’s life is good, meaningful, and worthwhile.” VeryWell Mind writes that there are different kinds of happiness (feelings of pleasure and of meaning) and generally two components to happiness: experiencing more positive than negative emotions and feeling satisfied with different areas of life. The Happiness Research Institute’s 2020 report shows that societies where citizens held a lot of trust in the community were better able to withstand crises, such as Covid-19.

Wellbeing Economy is one that values the wellbeing of its citizens equal to the traditional financial measure of gross domestic product (GDP), according to the Wellbeing Economic Alliance (WEAll), which is “a collaboration between governments, organisations, alliances, movements and individuals to transform the economic system into one that delivers social justice on a healthy planet.”

Everyone can join this collaborative movement for free at WEAll.org.

WEAll says, “Wellbeing is about the ability of everyone to lead a good life, not only the privileged, which means social and economic security, strong and lively communities, good working conditions and time for our friends and family.” Each of the six nations committed to a Wellbeing Economy are putting to place policies and practices to achieve those goals. Scotland’s take on it: “We are a society which treats all our people with kindness, dignity and compassion, respects the rule of law, and acts in an open and transparent way … This means building an economy that is inclusive and that promotes sustainability, prosperity and resilience, where businesses can thrive and innovate, and that supports all of our communities across Scotland to access opportunities that deliver local growth and wellbeing.” Learn more about WEAll in “Mental Wellbeing: The state of the world’s thoughts and feelings.”

Language is part of the solution

PHOTO Gary Barnes/Pexels

The perceived stigma around health issues is fading, but it’s not gone and it keeps people from seeking professional support, research shows. We can help ourselves and others by being aware of what contributes or detracts from our mental wellbeing and by the language we use. In the U.S.A., the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) invites Americans to join the StigmaFree Pledge to be a force for positive change: “Through powerful words and actions, we can shift the social and systemic barriers for those living with mental health conditions,” NAMI writes.

Each of us can help, too: The words we choose have the power to improve our own mental wellbeing and serve as a teachable moment for others. Let’s choose thoughtfully.

For more ways to be part of the solution, see Mental Wellbeing: How we can improve the world’s mental status quo.

Comments